Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) has probably been around for thousands of years. But it is only in the last hundred years or so that it has been recognized as a distinct psychological disorder. Its prevalence first came to public awareness during World War I. Front line soldiers in the trenches of Europe, who were the target of massive artillery barrages, were under constant stress, never knowing whether the next artillery round or bullet had their name on it. And this went on sporadically over several years.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) has probably been around for thousands of years. But it is only in the last hundred years or so that it has been recognized as a distinct psychological disorder. Its prevalence first came to public awareness during World War I. Front line soldiers in the trenches of Europe, who were the target of massive artillery barrages, were under constant stress, never knowing whether the next artillery round or bullet had their name on it. And this went on sporadically over several years.

It is not surprising that some men broke under the pressure. If the symptoms manifested at the front line during battle, there was a good chance that the soldier would be charged with ‘cowardice in the face of the enemy’ and summarily shot in front of his comrades as a lesson in discipline. If the thousand yard stare and erratic behaviour occurred after battle, while on leave or after the soldier returned home it was called ‘shell shock.’

The same thing happened in WW II, the Korean Conflict and the Viet Nam War. The condition started to become a matter of public concern in the face of television reporting during and after the war in Viet Nam. This is when some level of research started and ultimately the PTSD designation was applied. It is now recognized as a specific condition by most military forces in the world. In recent years we see more and more veterans of the Gulf Wars and ongoing military operations struggling with PTSD, both in the war zone and after they return home. It has been characterized by an increasing number of suicides among serving members as well as veterans.

But we need to remember that PTSD is not exclusive to the military. The intense traumatic stress that may trigger the condition can occur in civilian populations in a war zone, among people who experience natural disasters, and people who are the victims of sexual abuse or violence. This is particularly true if the stressful situation, over which the person has little control, extends over a protracted period of time.

What Is PTSD?

The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health says this.

It is natural to feel afraid during and after a traumatic situation. Fear triggers many split-second changes in the body to help defend against danger or to avoid it. This “fight-or-flight” response is a typical reaction meant to protect a person from harm. Nearly everyone will experience a range of reactions after trauma, yet most people recover from initial symptoms naturally. Those who continue to experience problems may be diagnosed with PTSD. People who have PTSD may feel stressed or frightened even when they are not in danger.

Symptoms can include:

Symptoms can include:

- Flashbacks—reliving the trauma over and over, including physical symptoms like a racing heart or sweating

- Bad dreams

- Frightening thoughts

- Staying away from places, events, or objects that are reminders of the traumatic experience

- Avoiding thoughts or feelings related to the traumatic event

- Being easily startled

- Feeling tense or “on edge”

- Having difficulty sleeping

- Having angry outbursts

- Trouble remembering key features of the traumatic event

- Negative thoughts about oneself or the world

- Distorted feelings like guilt or blame

- Loss of interest in enjoyable activities

Other ongoing problems can include:

- Avoiding relationships

- Substance abuse

- Panic disorder

- Depression

- Feeling suicidal

It’s More Than a Psychological Problem

The root cause of PTSD is a specific or ongoing traumatic stress-inducing event. We experience some level of stress every day. Some situations are more stressful than others. But traumatic stress raises the bar.

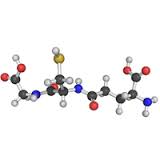

Cortisol is called the stress hormone because it is produced in response to a perceived threat. Cortisol’s effects are particularly noted in the brain, which make sense since the brain is the body’s control centre for the fight-or-flight response to the perceived threat. Many studies over the years have confirmed that prolonged increases in cortisol levels result in increased levels of free radicals. Therefore there is a risk that these radicals will cause damage to brain cells and, if significant enough, may result in altered brain function.

A recent study, involving military personnel as the subjects of the study, concluded that “oxidative stress, increased free radical level beyond excitotoxity, is a possible causal factor for clinical manifestation of PTSD.” (Ref. 1) Since many people with PTSD experience ongoing stress as a result of their symptoms, including re-experiencing the original stressful event, we can presume that additional damage may continue to be done if the level of free radical production due to the cortisol generation exceeds the antioxidant capacity of the subject. (Note: Oxidative Stress is a condition in which the level of damaging free radicals exceeds the anti-oxidant capacity of the body to neutralize them. A state of oxidative stress causes damage to the body’s cells and, if it persists, disease results.)

A Possible Way Forward

Current treatment involves medications and psychotherapy. People with PTSD are advised to seek competent professional help. Having a support network available and taking advantage of it is also strongly recommended.

However, given the possibility that PTSD symptoms are to some degree a result of physical brain chemistry issues due to oxidative stress, one wonders if tackling the oxidative stress situation head on might produce positive results. Increasing the body’s level of intracellular glutathione may be the key. Glutathione is the body’s master anti-oxidant and it is produced in every living cell in the body. Having optimum glutathione levels reduces or eliminates oxidative stress. There are several different ways to help the body increase its glutathione levels. Some are more effective than others; but none involve the administration of pharmaceutical drugs.

References:

Reference 1: Vladimirs Voicehovskis, et al, Oxidative Stress Parameters In Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Risk Group Patients, Proceedings of The Latvian Academy of Sciences, published 2012, Section B, Vol. 66 (2012), No. 6 (681), pp. 242–250. DOI: 10.2478/v10046-012-0016-x

#ptsd #healthscience #glutathione